ABSTRACT: The Washington Research Library Consortium (WRLC) is a regional library consortium of eight university libraries in the Washington DC and Virginia area. In 2002, WRLC built a Digital Collections Production Center (DCPC) to provide the technical and organizational infrastructure necessary to promote the development of digital collections among its member libraries. In its four years of operation, the DCPC has developed a sound organizational structure for building and sharing digital collections within the consortium and established unique services with a set of guidelines and procedures. This article describes the services, management, and technical infrastructure of the DCPC as well as the benefits of a centralized digital collection facility.

WRLC provides information technology services to its member libraries, including a shared information system known as ALADIN (Access to Library and Database Information Network), a library resource-sharing program for reciprocal borrowing based on a shared online catalog, consortial licensing of online resources, and a shared offsite storage facility that provides high-density, environmentally-controlled, retrievable storage for books, audiovisual or microform media, and archival boxes. (Payne, 1998)

WRLC member libraries host a verity of primary research materials in their special collections and archives. As digital library technologies are becoming increasingly available to academic libraries, the demands for converting special collections and archival materials into digital formats to make them widely available on the World Wide Web have increased. In 2002, WRLC expanded its services and built a Digital Collections Production Center with the assistance of a grant from the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to provide the technical and organizational infrastructure necessary to promote the development of digital collections among its member libraries.

This paper describes the services, management and technical infrastructure of the Digital Collections Production Center as well as the benefits of a centralized digital collections production facility.

The goal of this project was to create a shared facility to consolidate project management, information technology, and digital conversion experience in a production environment. (Payne, 2001) Major tasks of the project included hiring staff, selecting and purchasing equipment and software for digital conversions, selecting systems to manage and deliver digital objects, scanning materials selected from four sample collections, designing and creating Dublin Core metadata to describe digital objects, and encoding finding aids in Encoded Archival Description (EAD)[1] format. The outcome of the grant-funded project was a collaborative technical and organizational digital collections infrastructure, including a set of tools to facilitate the creation of digital collections, documentation describing the process and procedures, guidelines providing instructions and guidance for the member libraries to develop their digital collections, several experimental digital collections, and a finding aids database. (Zhang & Gourley, 2003) The success of this project demonstrated the value of an ongoing digital conversion service and encouraged the integration of DCPC into WRLC’s core services and operating budget in late 2003. Since then, DCPC is financed by the WRLC’s membership fee.

Payne, the Executive Director of WRLC, pointed out in the grant proposal that the organizational structure, procedures, technical and workflow guidelines, and partner relationships which WRLC seeks to define through this project should serve for other library consortia or distributed library systems which seek to collaborate on digitizing projects. (Payne, 2001) In its four years of operation, DCPC has developed a sound organizational structure for building and sharing digital collections within the consortium. A variety of digital resources representing the unique collections at the WRLC member libraries were made available to the students, researchers and general public. The procedures, technical guidelines, and workflow that DCPC developed have proven to be effective and flexible. The services provided by DCPC have demonstrated to be valuable to the member libraries. The WRLC’s digital collections and the underline digital library systems both became notable in the digital library community in the world.

The project agreement includes information about the owning library and contact person, general description of the physical archival collection, description of requirements for digital collection, delivery and retrieval plans for the original materials, special handling requirements if any, and a conversion schedule.

WRLC requires the owning library to affirm that it has the rights to digitize the material in the collection. In cases where works to be digitized are covered by copyright, the owning library is responsible for obtaining permission from the copyright holder to digitize and disseminate the works. A copy of the permissions document must be provided to WRLC along with the materials. (Payne, 2003)

In addition, the planning process involves scheduling time and staff for a particular project, sometimes for multiple projects, and communicating with staff in the WRLC Information Technology (IT) Services to discuss required support for setting up system, storage, and programming if needed.

The DCPC staff also works with libraries on projects where it may be more suitable to outsource the digital conversion to a service bureau, either because the materials are well-suited to batch processing or because they require specialized equipment (materials such as microforms, audio or video, or very large quantities of printed matter). In such cases, DCPC provides the project management, design, and descriptive metadata services, and is able to load the resulting files into the ALADIN digital library. (Payne, 2003)

In order to manage digitizing projects efficiently and properly, DCPC has developed a number of procedures, including guidelines for handling and storing original materials and procedure for receiving and safely returning the original materials. Workflows for each step of the digitization and metadata creation are documented in details and checked regularly to ensure efficiency and quality. DCPC also provides tools and instructions for member libraries to use for digitization and metadata creation when the member library has funding and staff available.

In the process of each digitizing projects, when a small number of items are digitized and related metadata are available, the DCPC staff designs and creates a preview web site for the owning library staff to review and give feedback. This helps the DCPC staff to adjust techniques in scanning and image conversion, and improve the quality of metadata, if necessary. This also avoids making more mistakes in a later stage of the project. When a project is completed, the DCPC staff sends a summary of the project to the owing library, including statistics of scanned images and metadata records, starting and completion dates for each phase of the project, and special notes. This summary helps the owing library determine strategies and develop more efficient plans for future digitization projects.

First, the original materials are carefully analyzed. The materials may have different physical structures. Some are single-page objects such as photographs, slides, art images, and so forth. Some are multi-page objects such as manuscripts, magazines, and books. Some objects have a hierarchical structure such as a book containing chapters which themselves contain articles. Some objects have both a horizontal and vertical structure. For example, a serial magazine may contain stories continuing in several issues while each issue contains several continued stories. Some objects are related to other objects, such as a photograph showing a journalist interviewing a musician, and an audio file of the interview. The audio object has its own metadata describing the interview, so the metadata for each object needs to reference the related item. Understanding the physical structure and characteristics of the material provides a foundation for the metadata design.

Second, the functions and navigations required for the user interface are outlined. Typically, a display page of an image would contain the metadata and a thumbnail of the image. When the thumbnail is clicked, a larger image is displayed. For multi-page objects, the image display needs to include links to the next and previous pages and to jump to any page image. Hierarchical and relational material structures require additional navigation. For example, for a serial comic book collection, a user may want to see the titles of each story, display an entire issue through the table of contents, or view all images in an issue from cover to cover. The user may also want to view a single story continued from issue to issue. All of these functions are outlined before starting the metadata design.

Finally, metadata is designed to facilitate the functions that are outlined. There are three types of metadata. Descriptive metadata describes and identifies information resources and supports discovery through search and browse functions. Administrative metadata assists both the short-term and the long-term management, and the processing of digital collections. Structural metadata facilitates navigation and presentation of digital resources by representing relationships between components, such as sequences of images. (Kenney et al., 2003). "Metadata schemes (also called schema) are sets of metadata elements designed for a specific purpose, such as describing a particular type of information resource". (NISO, 2004) Many different metadata schemas exist, some quite simple in their description, such as the Dublin Core (DC) [2], others quite complex and rich, such as the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) [3], Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard (METS) [4], Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) [5], and the Encoded Archive Description (EAD).

DCPC selected qualified Dublin Core (Hillmann, 2005) as the metadata schema for descriptive metadata. To assist with cross-collection searching and browsing, several elements, such as Identifier, Title, Subject, Type, Repository, and Collection Name, are to be entered in each metadata record. Local qualifiers are added, when necessary, to distinguish metadata that is refined beyond the core elements of the Dublin Core. The local qualifiers are created based on this recommendation from the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative: "A client should be able to ignore any qualifier and use the information as if it were unqualified. While this may result in some loss of specificity, the remaining element value (without the qualifier) should continue to be generally correct and useful for discovery" (Hillmann, 2005). Whenever possible, DCPC makes use of information about the original materials by mapping their metadata schemas and formats (such as MARC, Excel, commercial database, etc.) to qualified Dublin Core.

DCPC’s administrative metadata is designed to record the scanning location and date, scanning resolution, bit-depth, compression, and dimensions. These metadata do not generally display in the public interface, although box and folder information are typically included in a "Material Location" element which is displayed.

Structural metadata design has been one of the most challenging tasks in DCPC’s metadata design, as well as one of the most important. Many functions offered to the user depend on the navigational structure of the digital objects in the collections. For multi-page objects, in order to turn pages in sequence, structural metadata must identify the first page image and list the sequence of the other images. To go to a story in a comic book and view images only related to this particular story requires structural metadata that identifies the starting page number and the number of pages related to this story.

Informed by the use of a simple DIDL (Digital Item Declaration Language) profile at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (Bekaert et.al., 2003), DCPC chose MPEG-21 DIDL for representing the internal structure of the digital objects. A DIDL document is associated with each digital object and includes information such as the sequence number for each content file, web-addressable links to each file, and links to related objects. It also describes the kinds of files that make up the digital object, distinguishing, for example, web display images, thumbnail images, master TIFF images, and transcription text files that may all be part of a single digital object. The Dublin Core "Relation" element is used to encode external structure. External structure represents object-to-object relationships, such as the hierarchical structure of articles in an issue and issues in a volume of a serial publication. (Zhang & Gourley, 2006)

The DCPC’s staff creates metadata records using a template designed for a specific collection. In some cases when the owing libraries have staff and funding available for metadata creation, the DCPC staff designs the metadata and provides instructions for the library staff to create metadata records using DCPC’s tools. A great number of metadata records were created automatically in batch process using programs designed by the WRLC’s IT staff based on the filenames. DCPC also creates collection level records for each digital collection and enters theses records in the WRLC’s ALADIN system, which will be contributed to the national bibliographic databases.

In her digital imaging tutorial "Moving Theory into Practice", Kenney states that "technical infrastructure decisions require careful planning because digital imaging technology changes rapidly. The best way to minimize the impact of depreciation and obsolescence is through careful evaluation, and the avoidance of unique, proprietary solutions." (Kenney et al., 2003) To determine scanning specifications for each individual projects, the DCPC staff always carefully evaluates digital imaging technology currently available and the best practices. Uncompressed TIFF format was selected as the master file format, because "TIFF is the format of choice for archiving important images. TIFF is the leading commercial and professional image standard. TIFF is the most universal and most widely supported format across all platforms, Mac, Windows, Unix." (Fulton, 1997)

Following the general principles suggested by the Western States Digital Imaging Best Practices, DCPC scans at the highest resolution appropriate to the nature of the source material, scans at an appropriate level of quality to avoid rescanning and re-handling of the originals in the future, and creates and stores a master image file that can be used to produce derivative image files and serves a variety of current and future user needs. (Western States Digital Standards Group, 2003)

After the physical items are scanned, DCPC’s administrative metadata, such as scanning device, resolution, bit-depth and location, as well as the collection name and keywords, are added and embedded in the TIFF files. An ownership statement is added to the bottom of each image. All of these steps are completed through a batch process using the PhotoShop software.

Derivative files are converted from the master files based on material type and user needs. In general, for images such as photographs, handwritten materials, drawings, and slides, JPEG format is selected for display, because the JEPG format "is most frequently used for access images requiring lossy compression." (Western States Digital Standards Group, 2003) The conversion from the TIFF format to the JPEG format is made through a batch process using PhotoShop. For text materials, such as printed documents, articles in magazines, and print newsletters, searchable PDF format is preferred, whenever possible. The conversion from the TIFF format to a searchable PDF format is completed through a batch process using the Adobe Capture software.

DCPC also transcribes a small number of handwritten letters to readable and searchable text and creates HTML files for the transcriptions.

WRLC member libraries have created many finding aids providing access to the rich research resources in the special collections and archives. Most of the finding aids are created and maintained in diverse electronic formats and software, including MS Word, MS Excel, FileMaker Pro, MS Access, and some locally created databases. Some finding aids are in paper format only. These finding aids have been used mainly by the staff at the special collections and archives for inventory control. They are also used by users who come to the library to use the resources in the special collections and archives. As the Internet technology develops, libraries started to post their finding aids on their web sites. These finding aids, even though in a machine readable format, are scattered on each individual library’s web site and are not in a standard format that can be searched and retrieved world-wide.

To enhance access to the finding aids, DCPC developed a finding aid database using international standard EAD (Encoded Archival Description). EAD "is a set of rules for designating the intellectual and physical parts of archival finding aids so that the information contained therein may be searched, retrieved, displayed, and exchanged in a predictable platform-independent manner." (Society of American Archivists 1998) "EAD provides a means of structuring the language of finding aids, so that they may be processed for presentation on the web, and so that their descriptive elements can be exchanged with other metadata systems." (McCrory & Russell, 2005) Pitti, one of the founders of the EAD standard, noted a key advantage offered by EAD, "EAD makes it possible to provide union access to detailed archival descriptions and resources in repositories distributed throughout the world. . . . Libraries and archives will be able to easily share information about complementary records and collections, and to ‘virtually’ integrate collections related by provenance, but dispersed geographically or administratively." (Pitti & Duff eds., 2001)

DCPC follows the Recommended Best Practices for Encoded Archival Description Finding Aids at the Library of Congress (EAD Version 2002)[7] in conjunction with the EAD Tag Library (version 2002)[8] and EAD Application Guidelines,[9] both published by the Society of American Archivists and the Library of Congress. These guidelines also conform to the Research Library Group's RLG Best Practice Guidelines for EAD 2002.[10]

In addition to creating EAD finding aids for the collections that have been digitized, DCPC also develops mapping instructions for converting finding aids from different electronic formats into EAD. Based on the mapping instructions, the WRLC IT group develops scripts and programs to implement the conversions. As DCPC is not staffed to encode finding aids into EAD, an online EAD Form was developed to help the member library staff encode EAD finding aids. This online EAD Form was designed to provide a user-friendly tool for library staff who may or may not have training in EAD finding aids creation.

The WRLC member libraries maintain a variety of unique special collections that have been and will be digitized in DCPC or hosted in the DCPC’s digital collections, which are presented through the WRLC’s Digital Collections interface. The types of material include manuscripts, photographs, slides, full text documents, newspaper clippings, magazines, audio recordings and video clips, and others. Because of the diversity of the materials and contents, the digital collections require different indexes and field display labels for the metadata. In addition, due to the member libraries' participation in various overlapping projects and systems, each digital collection must be independent. It is very important to make the libraries' digital collections available across multiple environments and accessible through multiple channels. The libraries may use individual digital objects outside the WRLC digital library system for online exhibits or other purposes. Each digital object and related metadata needs to be independently accessible and in standard formats in order to be linked from other online systems. (Zhang & Gourley, 2003)

To meet the requirements for presenting and delivering the diverse digital collections, DCPC selected an open source system Greenstone Digital Library Software[11] to present the digital collections on the web. Greenstone provides browsing options and supports indexing and full-text searching. Each collection can be built independently using Greenstone so that individual collections can be linked from other online systems and used for other purposes.

Greenstone's user interface is workable and configurable, but in its default form it is rather basic. DCPC focused on customizing Greenstone to highlight the unique features of the individual digital collections. The metadata description is presented in a standard library OPAC format with a thumbnail image. Full-size images can be viewed with Image Viewer in another browser window. Full-text transcriptions in any formats are linked within the record and can be viewed through appropriate applications.

Greenstone's user interface is controlled by macros, which can be customized to modify the user interface. To make the interface more user-friendly and attractive, DCPC developed several new macros and redesigned all graphics to add different "flavors" to the individual collections.[12] The unique designs of the DCPC collections and works completed in customizing the Greenstone user interface were contributed to the Greenstone community to help other Greenstone users design and customize user interface. (Zhang, 2003)

The computing support infrastructure at WRLC is centralized. Responsibility for computer systems, disk- and tape-storage units, programming, and all aspects of server operations lies with the Information Technology Services (IT Services). The support of the IT Services is essential to DCPC’s operations. The IT group provides expertise in software/server testing, installation and maintenance, programming on demands, developing new tools and improving existing tools for creating digital collections.

Communication with the IT group is one of the major aspects of the DCPC management. Described by Umbach, "talking to technical staff is an art in itself." (Umbach, 2001) An article by Rossmann addresses, "much like any successful relationship, when technology staff and library staff take the time to understand how the other person views the world and keep open, clear channels of communication they can create a much more harmonious relationship than one where one’s own needs always take priority." (Rossmann, 2005) Effective communications between the DCPC and the IT group are based on mutual understanding and trust. To help the IT group understand what is requested from librarians’ or users’ point of view, the DCPC staff always tries to better articulate their needs and to find as much information as possible for the tasks they want to implement. Then, "let them do their job". The IT group is always reliable for delivering excellent supports and services.

Documentation is a very important part of the DCPC’s management. According to Western States Digital Standards Group, "documentation of the choices your project has made can be a key factor in the long-term success of digitization efforts. Good documentation can offset the impact of staff turnover and allow future staff an ability to deal with digital collections created by their predecessors." (Western States Digital Standards Group, 2003) DCPC documents major technical decisions made to digitize individual collections, including file naming convention, metadata design, functionality requirements of the user interface, data mapping, data input instructions, issues and problems resolved, etc. DCPC keeps good documentations for all projects, including project agreement, copyright status, original information about the physical collection and objects, statistics for scanning and metadata records, and so forth. These documentations have helped and will continue to help the management make decisions for maintaining the digital collections in the long term.

Production statistics are also very important for the management. "Used properly, they can highlight service gaps and opportunities and help us determine what to allocate for budgets." (Singh, 2005) DCPC keeps daily, monthly and yearly production statistics categorized by project and institution. These statistics have helped the management in decision making, project planning, scheduling, storage managing, quality control, and productivity managing.

The usage statistics for the digital collections are also collected and presented to the library staff through the WRLC’s intranet. The usage statistics provide helpful information on how often a collection is visited, how many times a digital object is requested, where the users come from, and what computing system they are using, which will assist the library staff with determining how to select their collections for digitization and help the DCPC management make decisions in interface design and software selection.

Collection maintenance is an ongoing management issue of the DCPC. DCPC works closely with the WRLC’s IT Services to ensure that the access applications remain usable and the data is up-to-date, to plan for future migration, to recommend new technologies and tools available, and to implement new standards.

All the digital collections are presented through the Greenstone Digital Library Software, which is a suite of software for building and publishing digital collections. Greenstone is produced by the New Zealand Digital Library Project at the University of Waikato, and developed and distributed in cooperation with UNESCO and the Human Info NGO. Greenstone provides a way of organizing information and publishing it on the web in the form of a fully-searchable, metadata-driven digital library (Witten & Bainbridge, 2002). Greenstone has been used to make many digital library collections in different countries, from different kinds of library, and with different sorts of source material (Witten, 2003; Witten et al., 2005). "Greenstone open source system is particularly important for digital libraries." (Lesk, 2005) The WRLC selected Greenstone as its presentation system to publish digital collections on the web after evaluating several systems against the selection criteria specified by WRLC to satisfy its organizational needs. (Zhang & Gourley, 2006)

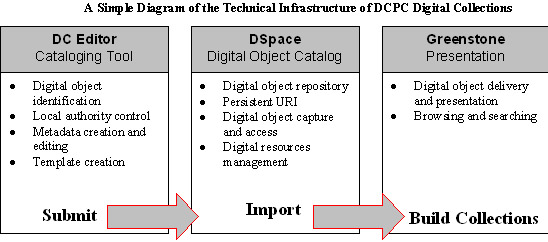

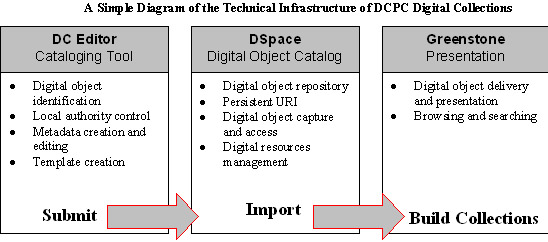

Data input and metadata creation at DCPC are implemented using a Dublin Core Editor (DC Editor) based on another open source software DC-dot. DC-dot is a web-based Dublin Core generator and editor, developed by Andy Powell at UKOLN, University of Bath, United Kingdom.[13] DCPC adopted the Dublin Core data entry form of the DC-dot, added several features, integrated it with Greenstone’s collection management tools, and are using it for the metadata creation and management interface. The features of the original DC-dot are limited. The WRLC IT staff enhanced this tool extensively. The current features of this metadata creation tool include:

In 2005, a new component, Digital Object Catalog (DOC) based on open source software DSpace[14], was added to the structure of the DCPC digital collections. DSpace is a digital repository system that captures, stores, indexes, preserves, and distributes digital research material. (Smith, 2005) The DOC provides a set of tools for helping DCPC keep track of their data and organize it in meaningful ways. DOC fits between the DC Editor and Greenstone. Based on DCPC’s needs and workflow, the WRLC IT group designed and developed programs to link DOC with DC Editor and Greenstone. After a record is created in DC Editor, one can click on a "Submit" button in DC Editor to submit the record and the associated image files to DOC, where the metadata record and associated image files are registered, stored, and are given a persistent identifier. The digital objects and metadata records in DOC are imported to Greenstone through a nightly process using scripts, and the collection is build in Greenstone automatically over night.

The following simple diagram illustrates the structure of the DCPC digital collections.

The success of DCPC has demonstrated that a centralized digital collections production center can break this major obstacle to implementing digital collections by providing shared facilities and a team of dedicated technical expertise in each step of the digitization cycle. Ongoing digitization activities in DCPC provide revenue for the technical expertise to retain and grow, which will be beneficial to implementing future digitization projects.

Digital resource management is another critical managerial skill that required for building and maintaining digital collections. "Collection maintenance may take different sets of skills and different commitments of resources than the original collection building. The digital repository must be integrated into the institutional collections management workflow." (Arms, 2000) Arms points out that aspects of ongoing maintenance include such functions as maintaining the currency of locations, ensuring the usability of access applications, performing data entry and data cleaning, keeping logging and accumulating statistics, providing some level of end-user support, maintaining server security, system administration, and so forth. (Arms, 2000) All of these require highly trained professionals in digital resource management.

A centralized digital collection production center can provide opportunities for staff to learn managerial skills in short time through the projects in their day-to-day tasks, thus providing quality managerial personnel to serve individual libraries’ digitization needs.

DCPC’s experiences present a model for sustaining digital collections in a centralized digital collection facility. Through concentrated technical expertise, combined financial resources, consolidated project management, and shared digital library systems, the individual member libraries can sustain their digital collections at lower and affordable prices.

A centralized digital production facility like DCPC supports smooth migration through a commitment to an ongoing set of process to move digitized materials through each generation of technology. Strict adherence to standards, sufficient documentation, and proper management are all possible and can be easily maintained in a centralized facility, which will make each stage of the migration smoothly and efficiently, and at the lowest costs.

A centralized digital production facility can provide constant support, guidance and models for the library staff to learn the process of digitization. DCPC helps the library staffs learn by guiding them through each step of the digital conversion, metadata creation and web site development, and presenting them with the final products. This learning process has proven to be more efficient and effective.

By introducing a consortial approach to building and sharing digital collections, this article describes the services, management, and technical structures of the centralized Digital Collections Production Center at the Washington Research Library Consortium. The success of DCPC demonstrated value of an ongoing digital conversion service and benefits of a centralized digital production facility.

[2]. Dublin Core (DC) is a general metadata element set for describing all types of resources. See Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) http://dublincore.org/

[3]. Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) is a metadata scheme for electronic text. See http://www.tei-c.org/

[4]. Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard (METS) is a metadata scheme for complex digital library objects. See http://www.loc.gov/standards/mets/

[5]. Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) is a metadata scheme for rich description of electronic resources. See http://www.loc.gov/standards/mods/

[6]. See Selected Finding Aids for WRLC Special Collections at http://www.aladin.wrlc.org/dl/collection/hdr?faids

[7]. Available at http://www.loc.gov/ead/practices/lcp2002.html

[8]. Available at http://www.loc.gov/ead/tglib/

[9]. Available at http://www.loc.gov/ead/ag/aghome.html

[10]. Available at http://www.rlg.org/en/pdfs/bpg.pdf

[11]. For more information about the Greenstone Digital Library Software, see Greenstone web site at http://www.greenstone.org/cgi-bin/library

[12]. View the WRLC’s Greenstone user interface at http://www.aladin.wrlc.org/dl/

[13]. For more information about DC-dot, see web site at http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/metadata/dcdot/

[14]. See DSpace web site at http://www.dspace.org/

Bekaert, Jeroen, Patrick Hochstenbach, & Herbert Van de Sompel. (2003). "Using MPEG-21 DIDL to Represent Complex Digital Objects in the Los Alamos National Laboratory Digital Library." D-Lib Magazine 9(11). URL: http://www.dlib.org/dlib/november03/bekaert/11bekaert.html

Clareson, Tom. (2006, February). "NEDCC Survey and Colloquium Explore Digitization and Digital Preservation Policies and Practices." RLG DigiNews. URL: http://www.rlg.org/en/page.php?Page_ID=20894&Printable=1&Article_ID=1815

Fulton, Wayne. (1997). A Few Scanning Tips. URL: http://www.scantips.com/

Hillmann, Diane. (2005). Using Dublin Core. URL: http://dublincore.org/documents/usageguide/

IFLA. (2005). Digital Libraries: Metadata Resources. URL: http://www.ifla.org/II/metadata.htm#general-indices

Kenney, Anne R., Oya Y. Rieger, & Richard Entlich. (2003). Moving Theory into Practice: Digital Imaging Tutorial. URL: http://www.library.cornell.edu/preservation/tutorial/contents.html

Lesk, Michael. (2005). Understanding Digital Libraries. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

McCrory, Amy, & Russell, Beth M. (2005). "Crosswalking EAD: Collaboration in Archival Description." Information Technology & Libraries, 24(3).

NISO (National Information Standard Organization). (2004). Understanding Metadata. Bethesda: NISO Press. Also available online at: http://www.niso.org/standards/resources/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf

Payne, Elizabeth A. (1998). "The Washington Research Library Consortium: A Real Organization for a Virtual Library." Information Technology & Libraries, 17(1).

Payne, Elizabeth A. (2001). Proposal to Institute of Museum and Library Services: 2001 National Leadership Grants for Libraries. URL: http://www.wrlc.org/diglib/dcpc/imlsproposal.pdf

Payne, Elizabeth A. (2003). WRLC Digital Collections Production Center (DCPC) guidebook. URL: http://www.wrlc.org/diglib/dcpc/Services/documents/dcpcguidebook.pdf

Pitti, Daniel V., & Duff, Wendy M. (Eds.). (2001). "Introduction." In Encoded Archival Description on the Internet. Binghamton, N.Y.: Haworth, 2001.

Rossmann, Brian and Doralyn Rossmann. (2005). "Communication with Library Systems Support Personnel: Models for Success." Library Philosophy and Practice 7(2).

Singh, Sandra. (2005). "Gathering the Stories Behind Our Statistics." American Libraries, 36(10).

Smith, Abby. (2003). "Issues in Sustainability: Creating Value for Online Users." First Monday, 8(5). URL: http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue8_5/smith/index.html

Smith, MacKenzie. (2005). "Exploring Variety in Digital Collections and the Implications for Digital Preservation." Library Trends, 54(1).

Society of American Archivists. (1998). EAD Tag Library for Version 1.0. URL: http://www.loc.gov/ead/tglib1998/

Task Force on Archiving of Digital Information. (1996). Preserving Digital Information: Report of the Task Force on Archiving of Digital Information. URL: http://www.rlg.org/legacy/ftpd/pub/archtf/final-report.pdf

Umbach, Judith M. (2001). "Talking to Techies." Feliciter, 47(5).

Western States Digital Standards Group: Digital Imaging Working Group. (2003). Western States Digital Imaging Best Practices Version 1.0. URL: http://www.cdpheritage.org/digital/scanning/documents/WSDIBP_v1.pdf

Witten, Ian H. (2003). "Examples of Practical Digital Libraries: Collections Built Internationally Using Greenstone." D-Lib Magazine 9(3). URL: http://www.dlib.org/dlib/march03/witten/03witten.html

Witten, Ian H., & Bainbridge, David. (2002). How to Build a Digital Library. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

Witten, Ian H., Allison B. Zhang, Tod A. Olson, & Laura Sheble. (2005). "Greenstone in Practice: Implementations of an Open Source Digital Library System." In Sparking Synergies: Bringing research and Practice Together at ASIS&T. Silver Spring: American Society for Information Science and Technology, on CD-ROM.

Zhang, B. Allison. (2003). Customizing the Greenstone user interface. URL: http://www.wrlc.org/dcpc/UserInterface/interface.htm

Zhang, B. Allison, & Gourley, Don. (2003). "A Digital Collections Management System Based on Open Source Software." In ACM/IEEE 2003 Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL 2003): Proceedings. IEEE Computer Society 2003.

Zhang, B. Allison, & Gourley, Don. (2006). "Building Digital Collections Using Greenstone Digital Library Software." Accepted for publication in Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 11(2).

| Zhang, Allison B. (2006). "Building and Sharing Digital Collections in a Library Consortium." Chinese Librarianship: an International Electronic Journal, 22. URL: http://www.iclc.us/cliej/cl22zhang.htm |